28 July 2015

Mating with two rooks and Yurik's other adventures

International Master Alexander Zakharov recalls the last White Rook tournaments of the Soviet era.

Instead of a preface

The nationwide White Rook school team tournament is among the most popular junior events in Russia. This is no laughing matter: the strongest children from every region of Russia gather for the annual showdown at the magnificent Dagomys resort, Russia's top officials come to see them, and the efforts of Andrei Filatov, president of the Russian Chess Federation, result in new countries joining the White Rook movement.

The White Rook has an incredible potential and, I am certain, a glorious future. But as we move forward, we don't want to forget the past – the history of this vital tournament. So let us go back to the years that preceded the devastating 1990s and that saw school team combats in which future champions were born.

This is the first part of an article about the victory of Moscow school 962 in the last White Rook held in the Soviet Union. The young Evgeniy Najer, currently the reigning European champion and one of the coaches of the Russian gold-winning women's team, played on the first board for that school. Another member of the team was the author of the article, IM Alexander Zakharov, previously one of Russia's strongest young players, a medalist of Russian and European youth championships and the winner of the 1997 World Youth Olympiad, and presently head of the Moscow chess school Etud (the Russian for 'chess endgame study').

The RCF website's editors really hope that other participants, medalists and, of course, winners of the White Rook's "golden age" will try to bring back their stories of old and share them with the readers. Indeed, no memories are more loved and cherished by a chess player than those of the school years spent with childhood friends by the beloved black-and-white board and away from it...

Dmitry Kryakvin

The birth of the "Legend-962"

The White Rook, the legendary competition among pioneers' teams (aged under 14) from secondary schools, played an important role in the system of training chess players of the USSR, the strongest chess power in the history of the ancient game. All future world champions and leading grandmasters participated in the White Rook, and the winners' names automatically appeared on the first columns of chess magazines and, most importantly, the Pionerskaya Pravda, a popular Soviet newspaper. The Etud chess school and its best alumni were not just a part of that legend: they were its last heroes. In June 1991, Moscow school 962 won the Soviet White Rook in Lugansk, and six months later the USSR was no more. But let us start from the beginning.

The chess school Etud opened in 1988. Sasha (Alexander) Zakharov went to the second grade that year, and Ilya Shasnov to the sixth. It so happened that Etud's students went to the same school, 962. Its irreplaceable director, Larisa Aleksandrovna Polyakova, encouraged all creative projects and, to be honest, thanks to them she even turned a blind eye to our pranks. A lucky chance brought us another interesting person, our Physical Education teacher Yuri Anatolyevich Ivanov (we called him simply Yurik). Yurik was strict, a real PE teacher with a dramatic boxer's past who used methods of education that were far from democratic. Hooliganism was common in our neighborhood, and that time period was conducive to its rampant spreading. Pretty bad conflicts occurred at the school, and we always did without the police, whose role went to our PE teachers led by Yurik. They resolved issues quickly and fairly, and Yurik not only managed the process, but also beat up on the culprits for educational purposes. Yurik enjoyed well-deserved respect and authority among both the "nerds" and the "ruffians."

But all his roughness vanished at once when he talked to me, Ilya and other chess players. Chess pulled Yurik like a magnet, he felt there was something in it that he was lacking. He could watch chess games for hours, he rooted for us and was ready to squeeze with his boxer's grip anyone who threatened our interests. For all that, Yurik didn't know how to play chess...

Yurik was Ilya Shashnov's PE teacher, and it was probably Ilya who told him that there were other chess players at the school and that a team could be set up. Yurik hardly understood the nuances, but felt that it was time to act. At the moment, the Kirovsky District (currently called the North-Eastern Administrative District of Moscow) was a backward provincial place, as far as chess was concerned: there was simply no one to promote it. That is why Yurik's energy, multiplied by the decent initial team, was rewarded. School 962, which opened in 1987, easily won the Kirovsky District's championship and gained the right to participate in the Moscow championship, which in turn was a qualification event for the nationwide White Rook.

School 962

Our first team's composition was as follows:

1st board – Ilya Shashnov. Even then, Ilya was one of Moscow's leading young players and had the first category rank (this corresponds to a rating of just below 2000), so our first board was absolutely fine. Furthermore, Ilya was an excellent team captain, responsible, disciplined and clear-thinking Yurik had an unlimited trust for Ilya, and this was where Yurik's intuition proved to be right again. The other members of the team obeyed Ilya completely and respected him.

2nd board – Misha Bernadiner. He studied chess at the Tigran Petrosian club pretty seriously and played at the level of a first-category player; combined with his natural talent and age, this was more than enough to "cover" the second board on a district level. Misha didn't recognize any authorities (except for Yurik, of course) and often ran into trouble. He was involved in a funny story that happened in the Moscow Championship's final among schools. But we'll get to that later.

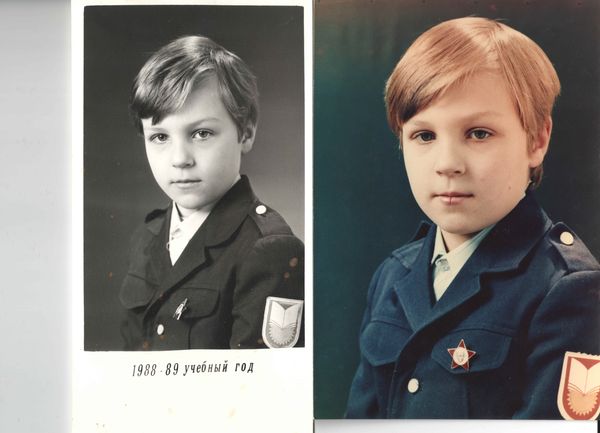

3rd board – Sasha Zakharov. I was only 7, but I already was a third category player, and I was becoming better with each game. Doing chess eight hours a day bore fruit. Of course, few people believed at first that a 7-year-old boy could do anything against the big guys. Yurik worried about the big age difference more than anyone else. But soon he saw for himself that there was some difference between chess and box after all and that the 7-year-old who was given the great honor to be on the team could work miracles.

The 7-year-old Sasha Zakharov

4th board – Serebryakov. His strength of play was between the third and the fourth categories, without any chance for improvement. Yurik acted very logically: when he was out of strong chess players who did chess at clubs, he set his eyes on the tough guys. Serebryakov had a bracelet and brass knuckles (the fashion of that raucous time), and that played a decisive role for Yurik. With hindsight, it can be admitted that this was a good and rational decision. At least we always had proper power support.

5th board – Serebryakova. The tournament was held in the 4+1 format: four boys and one girl, so we had to get a girl on the team. I don't know what made Yurik accept her, maybe the fact that she had the same family name as our fourth board player. She was a big, confident girl, but she played chess very badly: she knew the rules, she could move the pieces correctly, and that was about all. Her level of play was the fourth category at the most, and she had no interest in chess whatsoever. Serebryakova actually joined us only thanks to Yurik's charm. He probably rewarded her with excellent marks in PE.

Inspired by the easy win in the Kirovsky district, Yurik really spread his wings. Without sparing anything, Yurik invested his time, efforts, and even money in us. In fact, when we started playing in the Moscow Championship, Yurik gave the team members a daily allowance out of his own pocket to make sure that we ate and played well. Once Serebryakov spent this money on a Spartak badge (it was only then that football club symbols appeared on the market). Yurik noticed it and took some heavy-handed educational measures, after which he gave the hungry Serebryakov an ice-cream.

Our first Moscow Championship was the point at which all the other traditionally strong teams learnt that district Kirovsky also existed on the Moscow chess map. Even in the very first round, the lot fell upon us to face a team stuffed with the players of the Perovo school, which usually was easily among the top three Moscow schools. Our opponents' captain was in a very relaxed mood. We were looked upon as savages coming from the outskirts of Moscow. The first sensation took place just in two hours (every player had an hour for the game): school 962, which was known to no one, won the match with a score 3-2. We lost at once on the 4th and the 5th boards, but the first three held on like grim death. Yurik was behind our backs, and he was probably the only one who believed in a positive outcome. The decisive point was brought by the 7-year-old Sasha Zakharov, who defeated a first-category player much older than himself, thus throwing the opponents' team into utter bewilderment. Who were those children, where did they come from?

Very quickly, news spread among the coaches that the team of school 962 was led by a heavily-built man who didn't know how to play chess. Indeed, it was hard not to notice Yurik, a boxer among chess players! The results of our first Moscow Championship were quite promising for school 962. That time, our team made maximum use of its potential, given its composition, and finished in the top half of the tournament crosstable. We did miracles on the first three boards, while the last two players just came diligently for the games, scoring points when their opponents were absent or really weak. Yurik's contribution couldn't go unnoticed: thanks to his iron discipline alone, the team scored an additional two or three points along the distance. But the score showed clearly that winning in the White Rook was impossible without a balanced team. Those were plans for the future, however, and during the tournament the team members lived for the day and caused a stir not only at the chessboard.

The championship was held at the Olimpiyskiy Sports Complex, where the chess club was led by Valery Pavlovich Nazarov. By virtue of his office he was very touchy when any of the children tried to tamper with any chess property he was in charge of. Fate brought him together with Misha Bernadiner to offer everyone around an unforgettable scene. Valery Pavlovich, with his inherent meticulousness, filled in the crosstable with the White Rook's standings using three ball-point pens: blue, red, and green. When the competition was nearing its end, someone amended the immaculate table with their own marks. Valery Pavlovich was livid with indignation, and, standing by the table, he said: "What awful children they are! Who could do this? Ah, ah..." Misha Bernadiner, who was standing nearby and studying the table, responded immediately in a sharp attacking style: "That's an outrage! Ah, what an outrage! Ah, ah..." Valery Pavlovich's nerves failed this test, and his reaction was appropriate: "Are you making fun of me? You are going to answer for that!" Our Yurik was passing by and he only heard the last phrase, so familiar to him in his everyday life. Yurik took up the ball at once: "Who is going to answer? What questions do you have to school 962?" Misha stood back, Valery Pavlovich stumbled into Yurik's broad chest, the tension went down immediately, and school 962 further strengthened its reputation on the chess arena. To admit, Yurik saw into the matter out of public view later, and Misha was reprimanded severely, although without any physical disciplinary methods.

Our fatigue after the games was unbelievable, and we still had our homework to do after coming home late in the evening. But as we traveled back, we were allowed to toss coins that were left from Yurik's pocket money from the escalator at the Prospekt Mira metro station. When we descended, we tried to find those coins. This was fun, and Yurik encouraged us in that: our children's minds could relax so that our working capacity was at its height.

Interestingly, our fourth and fifth board players (they even shared the same family name – Serebryakov and Serebryakova), scarcely burdened with chess concerns, got attached to each other during the White Rook tournament. Yurik used this important aspect when forming the team for the next year. He proved to be a very good leader: we became a well-knit, solid team that was a threat to anyone who underestimated the Kirovsky district's champions. Like our PE teacher Yurik, those symbolic wings of love had nothing to do with chess, but without them the "Legend-962" would have never come to life. And we had a new 1989-1990 White Rook qualification cycle ahead of us.

Yurik's final stunt

When the Etud chess school opened in the Kirovsky district, the competition became much more fierce. The best young chess players came together under the roof of the new school and were in full view of its founder, Alexander Petrovich Bodisko. To Alexander Petrovich's credit, he felt the role that the White Rook could play in becoming famous across the entire Soviet Union, and with his usual energy and pedagogical skill he sprang into action.

The young Alexander Bodisko

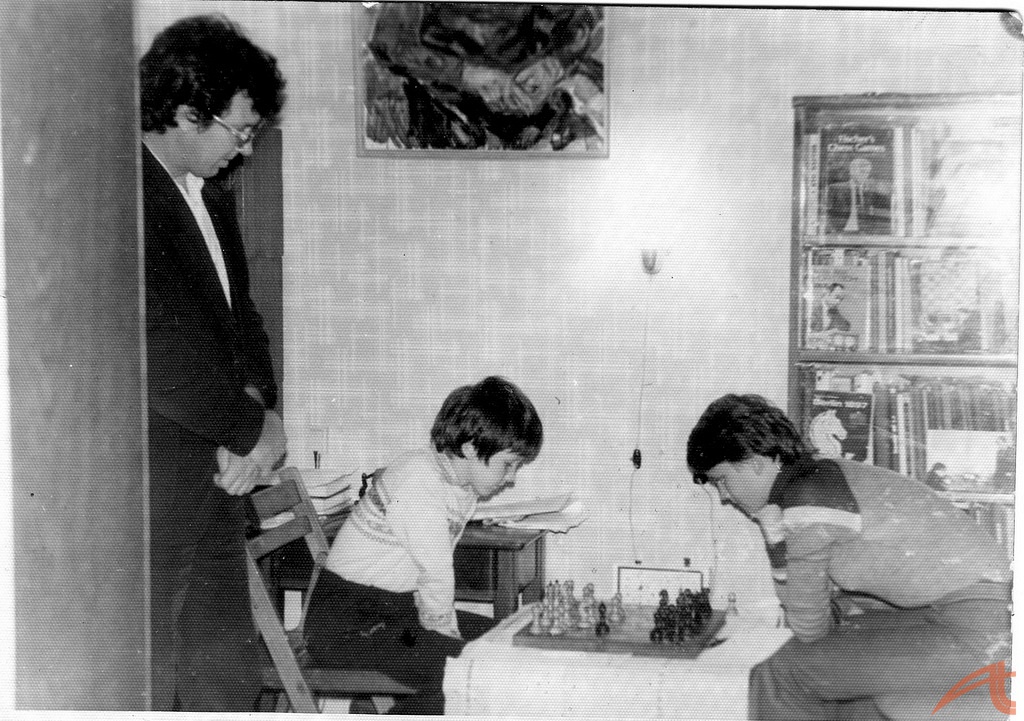

Alexander Petrovich only coached players of the second category and above, which was why I didn't get within his sight from the outset. Beginners were first trained in the Kirovsky House of Pioneers, and then coached at the Etud chess school by Leonid Vasilyevich Betin, who was suitably dubbed "The First Coach".

Leonid Betin and his students

The undisputable leaders under 14 were Evgeniy Najer, Ilya Shashnov and Sergei Bogatirevich. Evgeniy and Sergei lived in the neighborhood and went to school 606. Given this fact, Alexander Petrovich made a very logical decision: he used school 606 as the base for forming an Etud team to participate in the White Rook. The composition of the 606 school team seemed to make its victory in the Kirovsky district a very likely event:

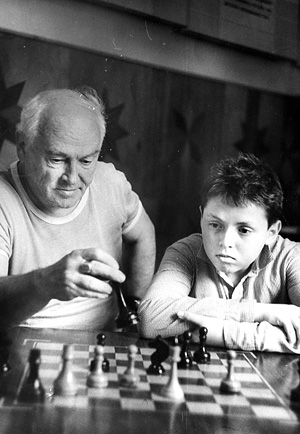

1st board: Evgeniy Najer

Evgeniy was the newly opened school's best student, and even then his fantastic talent, his excellent human qualities and devotion to chess were beyond any doubt. The first board was ready to participate in a competition of any level. Evgeniy already was a very strong candidate master.

Alexander Petrovich coaches Evgeniy Najer

2nd board: Sergei Bogatyrevich, a combination of fantastic energy, all-around erudition, and, of course, excellent chess skills. The first-category player Sergei was a year older than Evgeniy and Ilya, which played an important role at that stage. A very strong 2nd board.

3rd board: Pukh. I don't remember his first or family name, but his nickname was Pukh. He was a second-category player, and a senior high school student, which was considered a good finding at district-level competitions. Pukh's main achievement was making a Monopoly game with his own hands. We played this game in two teams of two during the time free from chess. Alexander Petrovich didn't approve of this capitalist influence and contemptuously called the Monopoly "diddle-daddle".

The 4th and 5th board players were just like our Serebryakovs from school 962, so in terms of chess level there was full equality between the schools here.

An encounter between schools 606 and 962 was inevitable, as well as Alexander Petrovich's meeting with Yurik...

In 1989, the chess school Etud was already the venue for the district White Rook, of course. By that moment, Alexander Petrovich built a vertical power system of governance, got all strong players under his wing and almost fully controlled the situation in terms of the young players' preparation level. According to his estimates, school 606 was supposed to defeat school 962 in the main qualifying match, and then he planned to add a few Etud students to the team before the Moscow Championship.

We had already met each other during our studies at Etud, and we discussed our chances for a while before the qualifying match. Our competition hoped to score quick wins on the first three boards, and there was no doubt at all that school 606 would win on the third board (Pukh was older and more experienced than me), while Evgeniy and Sergey were supposed to show their best play: in general, they were a little stronger than Ilya and Mikhail. Alexander Petrovich had the same plan and prepared his team vigorously for the district match of the year. The die was cast.

The situation in the tournament, which took place at the beginning of the school year, was absolutely predictable. Before the final playing day, schools 606 and 962 were leading by a wide margin, and the outcome would be determined in the face-to-face encounter. Alexander Petrovich provided full chess support to school 606 on home turf. Yurik ensured rigorous discipline and team spirit and inspired us all with his confidence.

Alas, our PE teacher was unable to give us purely chess support. The role of the chess coach of school 962 went to Ilya Shashnov's father, Gennady Anatolyevich, who was a very strong candidate master and, of course, couldn't stay aside at this crucial moment of the competition. He saw the most important thing: we needed to maintain the balance on the first three boards, and our boards 4 and 5 were a bit stronger, which should be enough for a victory. Ilya invited me to his place the day before the match (we lived within two minutes' walk away from each other), and we prepared thoroughly for the games under Gennady Anatolyevich's guidance. The master plan was as follows: Ilya was supposed to neutralize Evgeniy in a tenacious fight, and my task was to take my time, play the opening solidly (Gennady Anatolyevich's advice really helped me here), and then look how strong Pukh was and consider the match situation on the other boards. Misha Bernadiner was a person who was hard to train, so we decided to stay focused and determine the match outcome with our own Etud forces.

The decisive match took place in room 1 of the Etud chess school. The tables stood along the back side wall, so school 606 was kind of "pressed to the ropes" from the very beginning. The teams arrived in their optimal composition, and Alexander Petrovich and Yurik were ready for the fight. Fierce battles flared up immediately on all the boards. The first blood was shed on the third board, where I was able to eliminate the experienced second-category player Pukh with apparent ease. Some time later school 606 came back: Sergei Bogatyrevich won. Ilya Shashnov maintained equality on the first board. The match went according to our plans: the score was 1.5:1.5 on the first three boards. We shifted our attention to the fourth and the fifth boards.

The wall whereby the match was played

Serebryakov stood better, but the opponents played so badly that we advised Yurik to offer a draw in that excruciating game. The reason was that Serebryakova was winning and had a huge material advantage. Yurik listened to us, and Serebryakov followed the team leader's instruction obediently. The score was 2-2, with a huge material edge on board five. The tension was at its peak!

Everyone gathered around the two badly playing girls: Alexander Petrovich, Yurik, the team members, and Gennady Anatolyevich and Sergei Ivanovich (Sasha Zakharov's father) who came after work to support us.

Alexander Zakharov and his dad

Serebryakova's material advantage converted into extra two rooks, and then it became clear that she didn't know how to checkmate with two rooks. Standing near the board, we could somehow prompt her what the best practices for such a checkmate were, and she got down to business with her usual confidence. The problem arose when the black king, moving diagonally, finally reached the last rank. Serebryakova put her rook under attack and announced confidently: "Checkmate!". The girl from school 606 was happy that her torments were finally over in the game she was fed up with and stopped the clock.

There was a pause, then Alexander Petrovich was the first to tune in: "There is no checkmate, the game continues!" Our chess logic told us clearly that if the game continued and the girl captured the rook, Serebryakova would in no circumstances be able to checkmate with the surviving rook, and a draw would ensue. And here came Yurik's moment of glory. He outlined our position loudly and clearly: "The clock has been stopped, the game is over!" We started to make noise, too.

Poor girls! For them, chess was something absolutely useless, and they didn't understand why so many males were crowding around that miserable board and squabbling. Their game turned out to be the crucial one! Alexander Petrovich measured Yurik with his eye, assessed the chess aspects and probably many other things and made a wise decision to recognize his team's loss in the game, and in the match with the score 3-2. School 962 won the qualifying tournament and obtained the right to represent the Kirovsky district at the Moscow Championship. Yurik, Gennady Anatolyevich, Sergei Ivanovich and, of course, all of us were happy and enjoyed the well-deserved congratulations. On the very next day, the 8-year-old Sasha Zakharov moved from Leonid Vasilyevich Betin's group to that of Alexander Petrovich Bodisko and started to do chess together with the senior children. And school 962 became a reliable springboard for those who aspired to participate in the Moscow White Rook tournament.

To be continued