3 June 2015

They did not return from the battlefield. Sergey Belavenets

Grandmaster Evgeniy Solozhenkin looks into the fates of Soviet masters died in battle during the Great Patriotic War.

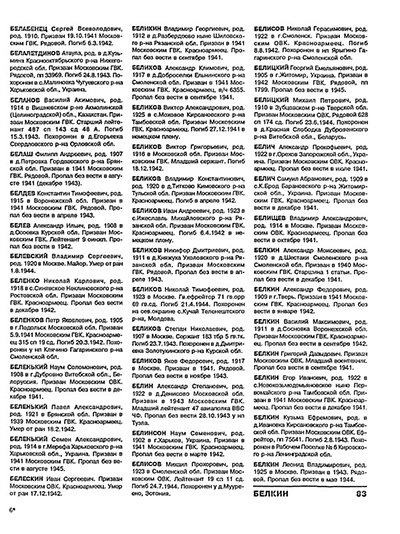

The first issue of 64 magazine in 1983 contained an article about Soviet masters Nikolai Riumin and Sergey Belavenets. After a while in the fourth issue the editorial office had to apologize to Liudmila Sergeevna Belavenets for the wrong year of her father's death. The article was signed by M.Yudovich, but it was obviously written by someone else. This someone else apparently drew upon the data concerning the years of life from Shakhmatnyj slovar ("Chess vocabulary") (pub. Fizkultura i sport, Moscow 1964), where the article about Sergey Vsevolodovich Belavenets had the year of death incorrectly noted as 1941. It is hard to imagine that Yudovich forgot the date of his friend's death.

It happened that I was once, almost accidentally, asked to translate a French document. It was a list of Soviet war prisoners, buried in Strasbourg cemetery. There were obvious mistakes in first and last names. I asked myself, if it is possible to find out their real names. I managed to find personal cards and other documents, which made possible to determine about a thousand names of Soviet war prisoners, buried and rested on the territory of modern Alsace, France. Then, thanks to the La Direction de la Mémoire du Patrimoine et des Archives (an analog of the Russian Federation Remembrance Authority by the Ministry of Defense) the tables in the Russian square of the South cemetery in Strasbourg were replaced. And the main thing is that 43 families (up to date) got to know the fate of their missing in action soldiers.

I would like to publish what I was able to find concerning the fate of Soviet chess masters, who were killed in battle. In some cases the documents of the Data bank challenge official time of death, and in other they help to clarify a burial place. For sure all the players who rendered life in the battle with foreign invaders regardless of their chess qualification deserve such a personal memory. But a man - on this occasion it is me - can do no more than he can. The masters fallen in battles were not so often recalled on pages of chess magazines during the postwar times. Let this article a little bit remedy such an injustice.

The first postwar issue of the Chess in USSR magazine went out already in May 1945. Particularly, the editorial said:

Semen Natov, Alexander Efremov, Mikhail Polyak, Nikolai Shutilkin – masters of sport in checkers (the magazine Chess in USSR was devoted both to chess and checkers, a couple of pages were devoted to checkers). Vasily Alexandrovich Sokov was the three-time USSR checkers champion, checkers master and also chess composer and candidate master, who took part in Leningrad championship 1943 during the Siege.

Of course, it was impossible to list all the experienced chess players who were killed in action during the war. Boris Stanishnev, who qualified as a master before the War but did not have time to do the necessary formalities, Mikhail Makogonov and Vladislav Silich were not mentioned among others. In 1935 the title USSR master of sports in chess was established. It replaced the title USSR master, which has been instated from 1925. In this regard the executive office of the All-Soviet Union chess and checkers section of High Council of Physical Culture (effectively the national chess federation) carried out an inspection of USSR masters qualification. As a result, 12 chess players were not re-attested. Later Makogonov didn't succeed in achieving a master norm, and Silich, on the contrary, achieved it and returned the honorary title. Yet he wasn't mentioned in Chess in USSR in May 1945.

Masters Sergey Belavenets, Mark Stolberg, Lev Kaiev, Vladislav Silich, and Mikhail Makogonov.

Let us remember them during the celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Victory in World War II.

Sergey Belavenets (1910-1942)

The most prominent master among they who were killed during the War was Sergey Vsevolodovich Belavenets.

Everyone who remembered him above all specified his unique personal traits – kindness, tact, willingness to help.

Belanenets (Belyj venets – "white wreath") is an old noble family from Smolensk region. The future master Sergey Belavenets was born in Smolensk. His ancestries of patriarchal lineage were naval sailors. The most prominent of them was Ivan Petrovich Belavenets (1829-1878), 1st rank Capitan, head of Kronstadt compass observatory, inventor of the compensation device, supporter of magnetic compass approach in the domestic fleet, author of fundamental scientific works in this field.

Before 1917 his portrait hung in the Central Naval Museum (Naval Museum of that time) in St. Petersburg. Ivan Petrovich Belavenets was a participant of the heroic Sevastopol defense, being a commander of an artillery battery.

Two brothers of Ivan Belavenets were also veterans of the Crimean War. Pavel Petrovich Belavenets fought in the Baltics, left the army being a lieutenant-commander. The lieutenant Nikolai Petrovich Belavenets was also a battery commander; he died on 24 October 1854 and was buried in Sevastopol. Grandmother of Sergey Belavenets, Nadezhda Nikanorovna Potjemkina came from the famous Potemkin-Tavritchesky dynasty.

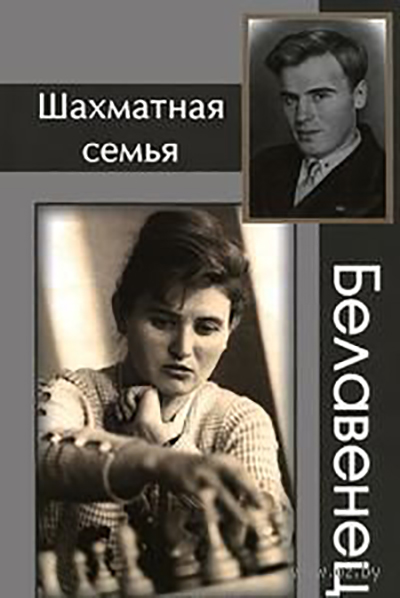

Only Sergey Belavenets' father Vsevolod Pavlovich was not a navy sailor. As all boys in the family before the revolution he entered the Naval Corps, but was excluded for ill behavior. Daughter of Sergey Liudmila Sergeevna Belavenets tells about it in the book "Belavenets chess family" written by Vladimir Barsky and Sergey Yanovsky (pub. "Andrey Elkov", Moscow 2012).

At one time Sergey Belavenets lived in a family of his aunt, his father's sister. His aunt's husband was Konstantin Alekseevich Vygodchikov, a famous Russian and Soviet chess player, multiple time champion of Smolensk, participant of Soviet Union events, USSR master (1929), later, however, he was downrated to the 1st category after the All-Soviet Union inspection of masters' qualification. The father of Belavenets, Vsevolod Pavlovich, liked correspondence play. It's clear that in such a home atmosphere Serezha couldn't stay away from chess. Soon he started showing good results. In the 20s he shone in various events in Belarus and Smolensk region. At the age of 14 Belavenets got the 1st category after winning the Belarus championship. Pre-war 1st chess category is a formidable level of skill!

In 1926 Belavenets moved to Moscow. He entered the university of agriculture mechanization and electrification, becoming an electrical engineer upon graduation. Later he managed to combine a regular job with playing in top-level chess tournaments, and various chess-related activities (he worked at the magazine "Chess in USSR" and was a coach in the Moscow Palace of the Pioneers). Constructions for collective livestock farms made by Belavenets were demonstrated in 1939 at the All-Soviet Union agriculture exhibition. Liudmila Sergeevna told that as it turned out her father had lots of scientific inventions, which found use after the war. His contributors regularly visited their house and brought money, explaining that without ideas of Sergey Vsevolodovich they wouldn't get their rewards.

When Sergey was a student, he studied chess and played a lot. In 1933 he became a master of sport. Belavenets finished first or joint first in Moscow championships three times. In 1937 and 1938 he was a champion. In XI USSR championship (1939) Sergey Belavenets finished third, surpassed only by Mikhail Botvinnik and the future grandmaster and Soviet champion (1948) Alexander Kotov, who took part in Candidates Tournaments twice.

Sergey Vsevolodovich Belavenets went down in history as a chess player of positional and maneuvering style. He longed to clear positions, it was even thought that love to clarity was his trait of character, and one of his most favorite expressions was "This is not logical!", as journalist Aleksander Iglitsky wrote. At the same time his analyses, which were published in chess periodicals, were often full of incredible tactical variations.

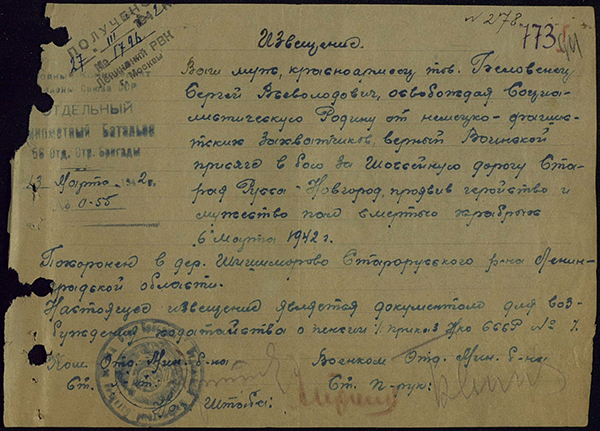

Sergey Belavenets sided with citizens in arms on 19 October 1941 according to the following document:

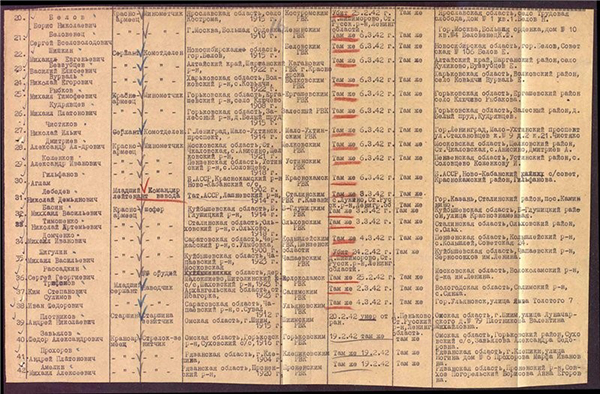

A Red Army soldier Sergey Belavenets fought as mortar gunner on the North-Western Front in the 56th separate rifle brigade of 11th army during the Demyansk Pocket. He died on 6 March 1942 near small village Shishimorovo located in Leningrad region (today Novgorod region), about 10 km from Staraya Russa, as it is written in the irrecoverable losses report:

He was 31 years old...

Liudmila Sergeevna Belavenets writes: "Circumstances of the death remain unknown".

From 6 March 1942 parts of the brigade moved to Shishimorovo and Malevo defense to the north, north-west and west.

From 6 March to 21 March 1942 parts of the brigade conducted heavy battles with the enemy forces attacking Shishimorovo on the side of Vereskovo and collective farm Novoseltsy.

During this period Shishimorovo went from hand to hand twice.

Sergey Belavenets was killed in battle for the Staraya Russa – Novgorod road, and that is the only thing known for sure about the circumstances of his death.

In 1957 remains of Red Army soldiers buried close to Staraya Russa including Shishimorovo were reinterred in the small village Nagovo. The Military memorial was built up on the reburial place.

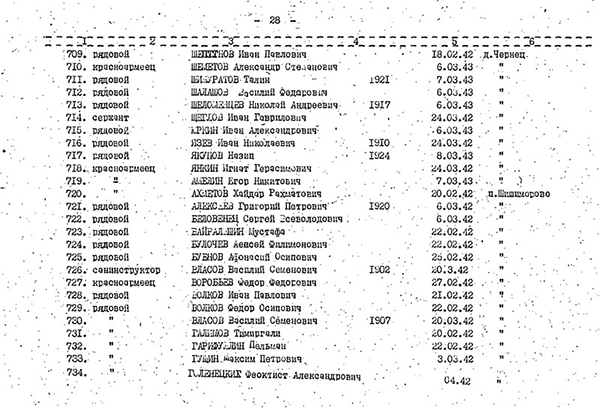

In the list of buried, which has more than a thousand of soldiers, S.V. Belavenets stands under the number 722.

Unfortunately there is a mistake in the spelling of the family name, confusion in ranks ("common soldier" replaced "Red Army soldier" in 1946). But at the same time Sergey Vsevolodovich Belavenets was in a sense lucky: at least his fate and burial place are known...

P.S. In April 2015 the Russian Chess Federation eternized memory of the master Sergey Belavenets, setting up a monument on his place of death.